Salmons and Crofts

Nana

Mabel Emily Salmon Croft

b. Cardiff, July 1893

d. Cardiff, November 1985

“Don’t cry for me Argentina

For I am ordinary, unimportant

And undeserving of such attention,

Unless we all are

I think we all are.”

Introduction

The most unusual thing about Mabel Croft, the maternal grandmother I knew as Nana, is that she was still going strong in her eighty-ninth year. That was a long life for a British woman of her time, and it allowed Nana to play an important role in my life. By contrast, my paternal grandmother, Evelyn Catherine Gilbert Scobie, died of cancer in 1940, two years before I was born.

In 1985, the Scobie-Croft family was beginning to think, rather resignedly alas, that Nana stood a good chance of living to one hundred and getting her telegram from the Queen. That telegram would have thrilled her to bits--Nana worshiped the royal family--but then, as winter came on, her chronic bronchitis, that had become almost a joke in the family, turned into pneumonia. She landed up not only in hospital for the first time in her life but hooked up to machines. In the night she tore out all the tubes and died without the night nurse noticing. Her husband Bob had died in much the same way in the same hospital decades earlier. This, at least, is the story passed on to me, and if I begin with it, it is because I inherited Nana’s chronic bronchitis and would like to think that, were life to get too hard to keep breathing, I might take things into my own hands as she did.

But if her death had something of the dramatic to it, my Nana’s life did not. Her biography could be summarized, objectively but not unkindly, as the uneventful life of an ordinary lower middle class British woman who devoted herself to family and was lucky enough to be spared most of the tragedies and traumas of her war-torn century.

Writing the uneventful life of an ordinary woman is a tough biographical assignment especially when, as is the case for my grandmother, she does not confess or self-analyze and leaves no written record of what she was thinking and feeling and doing. If I find myself attempting such a life now, it is because I cannot be objective about Nana. For my first ten or eleven years, she was my second mother, playing a bigger part in my life than my merchant mariner father. To me, Mabel Croft is special because I, her eldest grandchild, was her “golden girl”.

[Note: This is the expression used to describe me by Nana’s niece Jean Salmon Evans in a unique and unexpected letter to me following Nana’s death. I was astonished when I read this. When I was growing up, it was considered bad parenting to praise a child and “golden” was certainly not an adjective I would ever have used to describe myself. ]

As I think about Nana, I can see that I have very little more information about her early life than I do about my grandfather Bob’s, and yet I feel I know her as I did not know him. This is partly because I spent so much more time one on one with her when I was a child and she and I could and did talk, but more importantly it is because my grandmother lives on in me. She and my mother and I come from the same stock. But whereas, from the day my mother was born to the day Nana died, their two lives intertwined, and they competed with each other for soil and sky, I cut myself off, put out new roots in new soil, and grew into something different. In me blossomed a facility for words and a love of ideas that in my grandmother had been nipped in the bud, leaving in her as an undiagnosed, unassuageable discontent.

My Nana and I had a long and deep relationship. It was I that broke it, and now, in my ninetieth decade and with grandchildren of my own, I can see how that must have wounded her.

1. May Salmon and Her Family 1893-1907

Mabel Emily Salmon was born in 1893 in Roath, Cardiff. There she would live her whole life, rarely traveling farther than fifty miles away. There, her two children, Esme Catherine Croft and Thomas Alan Croft, were born, there, in the parish church of St Margaret’s, they were christened. confirmed and married. There I too was born, christened, confirmed, and married.

I remember Nana telling me when I was a girl is that she was one of ten children but, according to the parish and Census records, Nana’s parents, Edmund Frederick William Salmon (1853-1931) and Catherine Williams Salmon (1853-1939), had only eight children. In the family they were known as Tom, Polly, Eddie, Edie, Ernie, Alan, May, and Clem, and we can see them in this studio portrait that in 2024 Catherine Croft Rowland turned up in her father Tom Croft’s papers.

St Margaret’s, the parish church of Roath, reconstructed in the late 19th C to house a memorial chapel for the mother of the third Marquis of Bute. St Margaret’s church has some importance in this story because its parish records offer scraps of information about Nana’s life before I knew her. When I went on a nostalgia trip to Cardiff in 2021, I walked over to St. Margaret’s to try and get in, but the church was locked. I took a picture of the front of the church, whose porch forms the backdrop to so many family wedding photos, though, as we shall see, not of Nana and Bob’s. (Gill Collection)

Salmon family. (Croft Collection)

In the photo, Nana is the adorable little girl standing with her hand on her mother’s knee. She looks to be about four which would date the photograph to 1897/8. In front of Nana is her little brother Clement Norman (Clem), the last child in the family, born in 1895. The three young adults standing at the back are Thomas William (Tom), born in 1876, Mary Ann (Polly,) born in 1880, and Edmund Frederick (Eddie), born in 1878. The teenage girl standing on the right is Edith (Edie), born in 1886. The small boy seated on the left in the front is Ernest Walter, (Ernie), born in 1888, and the one on the right is Charles Alan (Alan), born in 1890.

When the Rowlands sent me this newly discovered photograph, it clarified the composition of Nana’s family of origin, but one thing still puzzled me. Another story I remember Nana telling me was that one of her sisters had died in her late teens of “galloping consumption”, yet the photograph shows only two older sisters, and I know they did not die young since I met them and members of their families. It seemed that either Nana or I had misremembered about the dead teenager, but then Maureen Gill, who so generously researched the Salmon family for me, discovered that Nana had had a half-sister, Emily Salmon. Edmund Frederick Salmon was married twice, and, since he married Catherine Williams in 1875, his first wife must have died around the time of Emily’s birth in 1873. Nana was born in 1893, so she did not know Emily, but her second given name was Emily, and the story of her half-sister’s illness and tragically young death was evidently passed on to her and she passed it on to me. I’m glad that strange phrase “galloping consumption” stuck in my memory and that Emily Salmon, one of the many thousands of young adults who fell victim to tuberculosis in late nineteenth century Britain, is therefore not totally forgotten.

Like the Crofts whom I introduced in my “Bob” chapter, the Salmons did not write diaries or keep letters, so little is known of Nana’s first twenty-three years, but she did share a few memories with me. Nana told me that she adored her oldest brother Tom—according to the Census he died in 1925, apparently unmarried and childless--but that the sibling she had been closest to was her younger brother Clem. All her life, Nana kept hold of this battered photograph of herself and Clem when they were young, and before Clem lost his sight in a bicycle accident at the age of twenty-one.

Nana added that she loved the sound of the cello, because Clem played the cello.

Nana and Clem probably dressed for the fancy dress party held in 1906 to celebrate the opening of Cardiff’s City Hall in Cathays Park. (Gill Collection)

From the tone Nana used when speaking of her younger brother and from the way she turned the radio dial as soon as a snatch of instrumental came on, I vaguely assumed that Clement Salmon was long dead. Thus, it came as a shock when, at some point in my late teens, after our family had moved to Kimberley Road, I opened the door to find two men on the doorstep, both wearing dark glasses and carrying white canes. They announced that they were my great uncle Clem Salmon and my cousin Tommy. They lived just down the hill, they explained, and had decided to call in since they happened to be passing. In some confusion I ushered the two men into the hall and called to my mother and grandmother to come. This was the first time I had ever been close to a blind person, and I remember that the sight of the younger man’s eyes wandering about behind the glasses unnerved me.

My mother appeared and, after a few minutes of desultory conversation, ushered out by my mother, and I was left with a host of questions. As a general rule, of course, I knew that unexpected visitors were unwelcome in our house—I think they made my mother see the deficiencies in her housekeeping—but this seemed a special case. Here was a great uncle of mine not only very much alive but blind and living just down the hill who should surely have been asked to sit down in the dining room and have a cup of tea. And if Uncle Clem was Nana’s favorite sibling when she was young, why would she not even speak to him now?

Nana’s brother Clement (right, on the cello) with his musical ensemble. (Croft Collection)

I learned from my mother that, though the visit of the two Salmons took her by surprise, she had always known that her uncle Clem and his family lived in our neighborhood, but Nana had broken off relations with them years before and refused to go to their house or allow them in hers. The quarrel between Nana and Clem began when, in his late twenties, he chose to marry Gladys? Clem Salmon had been blinded in a bicycle accident when he was twenty-one, but Gladys had been blind since birth. Worse yet, Gladys was “chapel”—that is not a member of the socially more prestigious Church of Wales--and when Clem became a devout member of the Plymouth Brethren like his wife, his family, including my grandmother, were upset. Things got worse when Clem and Gladys, who struggled to keep body and soul together, followed the beliefs of a sect that frowned on birth control, and started a family in the full knowledge that Gladys’s blindness was a heritable trait. Their first child, Jean, had normal vision but the second, Thomas, was born sightless like his mother—and at this point my grandmother apparently threw up her. High Anglican hands and refused to have anything more to do with them. If her brother chose to survive on charity and live in squalor, it was his own fault.

For my mother, Nana’s vendetta against her brother for becoming “chapel” and deliberately fathering a blind child was a real problem. She herself visited her uncle and his family and became, as I later discovered, a good friend to her cousin Jean, the only sighted person in the family and carrying an extraordinary domestic load. I wonder now if that unannounced visit of Clem and Tom Salmon soon after we moved to Kimberley Road was an effort on their part to heal the breach between the families now that Nana was a widow living under her daughter and son-in-law’s roof. If it was, it did not work. My grandmother was intransigent, and my mother was never able to invite the Clement Salmons to our house, so my siblings and I never got to know them. This was our loss as they were highly intelligent and cultured people who refused to be defined by their physical handicap. Jean and Tom Salmon may have been the first members of the extended family to go to college and get a degree.

I have dwelt here on the story of Nana and Clem because it has a moral--that physical proximity is no guarantee of emotional intimacy--and, as I strive to keep the bonds of my international family strong, I need to hold tight to that moral. My grandmother had brothers and sisters living close to her, some as close a block, but there was little love among them that I could see as a child. Nana lived by an unwritten code of familial hierarchy whereby there were financially struggling Salmons she would not greet on the street like Uncle Clem, poor Salmons she condescended to make use of like Auntie Edie, affluent Salmons like Uncle Alan whom she met only at funerals, and Salmons like Uncle Ernie she had anathematized, and this hierarchy mattered because it was passed on. Unconsciously, my grandmother and my mother regarded the men they loved and had chosen to marry as lower-class persons whose relatives, the Jarrow Crofts/Grieves and the “Tiger Bay” Scobies/Gilberts, had, as much as possible, to be ignored and kept at a distance. For my father, who shared a household with his mother-in-law for almost all his married life, this hierarchy within and among the families was, I believe, a source of constant, hidden domestic conflict. For me and my sister and brother, it meant that there were Salmon and Scobie uncles, aunts, and cousins in the immediate vicinity whose existence we did not even suspect.

Social snobbery was, and is, of course endemic in British culture, but Nana seems to have come by it rather indirectly. One story she passed on to me was that her family had come down in the world, and through no fault of its own. Her father, she told me, had once owned a prosperous inn in a valley near Cardiff, but he had lost his home and his business when the valley was flooded to create a reservoir. This story, I have recently ascertained, is based on solid historical fact. Several valleys near Cardiff were indeed flooded in the final decades of the nineteenth century to secure the water supply of the growing city and port. Frederick Salmon presumably got some kind of financial compensation for the loss of his inn, but that did not make up for the fall in status. My great grandfather had to move his growing family into a rental and take a job as warehouseman in the wine and spirits industry, and it would be a struggle before he had the means to buy a new permanent home at 60 Richards Terrace. Nana herself had never known life in the inn, but her parents and older siblings seem to have kept golden memories of it, and part of her Salmon heritage was a feeling of being better than their neighbors and an anxiety about maintaining the family’s place in middle-class society.

One last thing about the Salmons—not one I ever heard about from my grandmother, but one that may have had some bearing on the Salmon family’s assumption of social superiority. Maureen Gill, in the internet search she has done on my behalf, discovered that in recent years there has been a flurry of genealogical research reports on the large clan of Salmons in Jamaica that dates back to the mid- eighteenth century. Jamaica was at this time a notorious center of the pirate trade, and, to combat this, the British government decided to set up the sugar industry on the island. Sugar was one of the most profitable cash crops of the period, so large estates were granted to English colonists with the mandate to grow sugar, and a new generation of African slaves was shipped in to work the fields and refineries. Several male Salmons, including my own very distant ancestor William Salmon (b. 1743), took advantage of the British government’s largess and acquired considerable property on the island. When the first Salmons arrived there was an independent and rebellious enclave of Black freemen and freewomen called the “Maroons”, and William Salmon took as his common law wife Mary Vassall, a Jamaican woman of mixed race who gave him several children.

Over the next decades, Jamaica became what one historian of slavery has called “the blood-drenched epicenter” of the trade between Africa and the Caribbean. Such was the level of unregulated abuse it has been estimated that a higher percentage of enslaved persons died during the voyage to Jamaica and then on the island’s plantations than anywhere else in the world. But sugar became ever more in demand and the British nation profited hugely from its trade so, over the course of the next years, the Salmon family prospered and multiplied.

The tide began to turn in the early nineteenth century, when the British parliament abolished the slave trade in its empire, and, some thirty years later, abolished slavery itself. It had taken several generations, but British society finally found it advantageous to condemn and regulate the murderous labor practices of the Jamaican sugar magnates, and the Salmon clan splintered. Thomas Salmon (1803-1874), a grandson of the first William Salmon, left Jamaica and settled in Bristol where his grandson Edmund Frederick William Salmon (Nana’s father) was born. How much of the sugar fortune was inherited by this Bristol branch of the family and brought back to England is not known, but some folk memory of the good old days when the Salmons were wealthy Jamaican plantation owners may have been passed down.

I had a special reason to be interested in this plantation history. Many of my family members have thick, dark, tightly curling hair, and my research into social history had long led me to suspect that in my family’s history, as in so many other British families, there had been an African or Afro-Caribbean ancestor. I now can give a name to that ancestor--Mary Vassall.

2. The Years Before Marriage 1907-1915

At the age of fourteen, Mabel Salmon Croft left school and began fulltime employment as apprentice to a milliner. As Nana explained it to me, she left school because she was never able to master her times tables, and I can imagine what a relief it was to be spared the humiliation of failing to shoot out “forty-nine” when the Teacher yelled, “Mabel Salmon, what do what seven times seven make?” But the decision to take May out of school in her mid-teens was probably made by her parents for basic economic reasons. For a lower middle-class girl, at that period, ten years of schooling was considered generous and even boys typically entered the work force as teenagers. As we saw in the “Bob” chapter, Mabel’s future husband Reuben Croft left school at eleven. In 1907, Nana’s parents were still struggling to get back on their feet after the loss of the inn, so even May’s little pay packet would make a difference.

But if leaving school at fourteen seemed both normal and rational to Mabel Croft and her family at the time, and even though she turned out to be good at trimming hats and probably liked the hat shop better than the schoolroom, the long-term effects of ending formal education so young would be profound for my grandmother. Despite her problems with the times tables, she was not at all a stupid girl, and it is to her that I attribute my gift for language and my skill with argument. But whereas at age twenty I was opening my mind by reading Modern and Medieval Languages at Cambridge and traveling Europe, my Nana was living in a world of narrow culture and endemic racism which cookie-cut her into the shapes of daughter, wife, and mother. As we shall see, for Mabel Croft as for many other women before and since, those roles were not enough, would in fact lead to depression and orneriness and an inertia lit up by flashes of rage.

For the next eight years, as far as we know, Mabel Salmon worked as a milliner, and this was a period in her life my grandmother never reminisced about. From what she did say, I gathered that she continued to live at home under the authority of parents who, well after the death of the old queen, were stuck in the age of Victorian propriety. One anecdote Nana passed on to me was how she once dared to venture out of doors without a hat and her father slapped her face and sent her back inside. Nana taught me music hall songs, but when I asked her what music halls had been like she told me she did not know since her parents had never allowed her to go. Music halls were just not respectable. Nana never expressed any resentment toward her parents. On the contrary, I think she espoused their moral and social code--which makes all the more surprising the next milestone in her life, her marriage to Bob Croft in May 1915.

3. Marriage and Early Married Life. 1915 --1931

As I have recounted in the “Bob” chapter of this Memoir, Reuben Henry Lewis Croft, known to everyone as Bob, was the son of a working-class family in Jarrow, a busy industrial port in the far north of England. He left school at eleven to train to become a professional soccer player and came to Cardiff at some point in the 1910s to play for the Corries, the Cardiff Corinthians. Professional soccer players were paid only during the season and, according to his son Tom, Bob supported himself off the field by, variously, pulling teeth and painting dock gates. On his wedding certificate, his occupation is actually listed as dentist. Throughout his life, Bob was a sporting man, more often seen at the racetrack and in the club than in the pew, and thus hardly the kind of son-in-law Edmund and Catherine Salmon were looking for--assuming that in fact they were anxious to have this useful last daughter leave the nest. May Salmon was a docile young woman who had always bowed to her parents’ wishes and yet, when Bob Croft roared into her life on his motorbike, she rebelled and married him.

Bob as a young man. (Gill Collection)

The wedding of Nana and Bob took place in May 1915, and my cousins the Rowlands recently turned up several photos taken, they believe, at the time of the marriage. Seeing these photos surprised me, I would have expected to find copies in the small set of papers Nana left at her death, but they are not there. My unsubstantiated best guess is that Bob entrusted the photos to his son for safekeeping because, indirectly, they tell a story he wanted told and Nana did not.

Bob and Nana’s wedding took place some six months after the beginning of World War I, and in the photo below Bob is in his Royal Ambulance Corps uniform while Nana is wearing a lacy blouse with a pretty pendant or locket round her neck.

Bob and Nana, studio photo presumed to have been taken on or around the time of their May 1915 wedding. In the photograph here, Nana stands on the left wearing a smart suit jacket over the lacy blouse, and she and the two women with her wear gorgeous hats she probably trimmed herself. (Croft Collection)

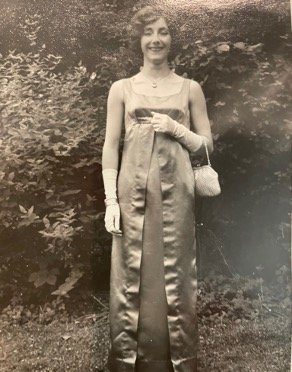

Nana at the time of her wedding. (Croft Collection)

In the photo above we can see Nana’s necklace more clearly, and I wonder if it might have been a wedding gift from the groom and possibly a Croft family heirloom brought by the woman standing next to her whom I identify as Mary Anne Croft Clark, Bob’s older sister. If I am right, Mrs. Clark must have come down specially to Cardiff from Jarrow to attend her brother’s wedding, meet his wife-to-be, and perhaps serve as her maid of honor. As for the third woman in the photo, she is too young to be Edie, the younger of Nana’s two older married sisters. My guess is that this is Alice Maud Preston whose name appears on the wedding certificate as one of the two witnesses and was presumably a close friend of the bride.

It is always perilous to make assumptions based on evidence that is NOT there but to me it is significant that the papers I inherited from Nana include a wedding certificate, stating the marriage took place at St Margaret’s church, but no wedding photograph. Only in 2024 have three photographs turned up in Tom Croft’s papers that appear to date from the time of his parents’ wedding, and they show only the bride--in a suit not a wedding dress-- the groom, the groom’s sister, and a woman who was presumably the bride’s witness.

The lack of a group photo taken at the church is odd. Even in 1915 and even among people of slender means, it was standard practice for families to commission a group photograph of all the wedding guests, often standing outside the church porch. I will be including two such group pictures l later in this chapter and I could have added my own. People do lose precious things of course, but Mabel Croft managed to hold on to the invitations she and her brother received to the 1906 civic celebrations, to the battered sepia photo of her and Clem as teenagers in fancy dress, and the barely decipherable snap of Bob on his motor bike. Bob, on the other hand, whose “papers” consist of one signed postcard-photo of himself, kept hold of these presumed wedding photos.

Every British marriage needed two witnesses to be legal, and, according to my grandparents’ wedding certificate, their two witnesses were Alice Preston and Clement Salmon. Could it be that Nana’s wedding party consisted of five people—the four in the photos plus her brother Clem? Could it be that Clem, the sibling she was closest to in her youth, was the only one of Nana’s relatives--all of whom, unlike Bob’s sister from Jarrow, lived close by-- who came to her wedding. Could it be that for Nana those absences were too painful to remember so she lost or destroyed the studio photos taken at the time. But for Bob, whose papers” consist of a signed photograph, those marriage photos commemorated an insult he would never forget so he kept them and passed them on to his son whom he trusted not to lose them.

Whether May’s family liked it or not, she and Bob Croft were man and wife, and the fact that the nation had declared war on Germany and Bob was in uniform and would soon be in the field were probably factors in their rush to the altar. One piece of my grandfather’s life that still needs to be researched is how long he served with the Royal Ambulance Corps, and when and how he suffered the knee injury that took him out of active service and also ended his professional soccer career. But one thing is certain, Bob Croft was back in Cardiff toward the end of 1917 since on October 18, 1918, my mother Esme was born.

Her birth, my mother once told me, was difficult since she was not only late and large but breach—a fact only discovered when Nana was already in labor. A breach birth in 1918 was not the horror story it had been in Berlin in 1859 when Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter gave birth to her first child, the future Kaiser, but even with anesthesia and special forceps, it was a nightmare experience for the parturient and it had physiological and psychological effects. Mabel Croft, whose mother had over some twenty years given birth to eight children, had only one more child, her son Tom, born in 1926. Again according to what my mother told me, Tom was nicely head down and gave Nana little trouble, and the contrast between those two labors and deliveries shaped the relationship my grandmother had with her children.

Her daughter Esme was the earth beneath my grandmother’s feet and the roof over her head, but, as I can testify first-hand, her son Tom was the sun in Nana’s sky and the song in her heart. My mother lived with her mother from the day she was born to the day Nana died. but they were forever at odds, pushing each other’s buttons, and scoring points off one another, as I have tried to capture in “Tea with the Scobies”. In contrast, my uncle Tom knew how to jolly his mother along, putting a glass of sherry in her hand at family parties and making her laugh. In her eyes he could do no wrong. As I have heard my mother bitterly remark after the Tom Croft family had closed our front door behind them, Nana’s face would light up every time “our Tommy” chose to come over for a visit.

Nana’s parents, Catherine Salmon seated, Edmund Salmon standing and holding a child, probably my mother Esme, and Nana’s blind brother Clem. I have not been able to identify the young woman. (Gill Collection)

Grandma Salmon with my mother, aged about 2. (Gill Collection)

After the war, Bob and May Croft set up house in rentals in Roath. This was where May’s parents and several of her siblings were living and, for a young family like the Crofts, Roath was ideal. A booming new middle class garden suburb, Roath was well inland and thus insulated from “Tiger Bay”, the grubby, dodgy, multi-culti docks area from which Cardiff derived its prosperity (and where my father’s family, the Gilberts and Scobies had its roots.) Roath had good schools and excellent recreational facilities, and the latter were especially important to Bob and his children, both of whom turned out to be athletic and good at games like himself.

Roath is where I spent my first nineteen years, so I can’t help adding, that was not until I went on a quick nostalgia trip to Cardiff in 2021 that I really saw its beauty. Roath has a string of parks which thread along a stream from a large recreation ground, through three differently planted flower gardens, and then on to an artificial lake big enough for row boats and frequented by wildfowl. Roath’s parks remind me of the Olmstead green necklaces in the U.S., and they still draw upwardly mobile families to Cardiff today.

Little is known of the period 1918-1931 in Nana’s life and Nana left only three tiny, blurry snaps which, as far as I can make out, show her parents with my mother aged about two. I reproduce two below., apparently taken on the same occasion and not, I believe, at Richards Terrace.

This was an era when married women of the middle class were expected not to work outside the home, so Mabel presumably gave up her job as a milliner and allowed Bob to fulfill his traditional role as the family breadwinner. Fortunately, the injury to his knee did not prevent him from doing this, and I have heard Nana boast that Bob brought his pay package home to her every week unopened. This was presumably something few other husbands did. Bob was also that rarity-- a gambling man who paid his personal expenses out of his winnings at the club and the track, and never went into debt. The Crofts were not rich and their prospects of saving enough to own their own home were poor, but they were respectable, and their children were clever, handsome, and thriving. And then, the Croft family. fortunes took a decided turn for the better.

4. Her Own Home.

In early 1931, Mabel’s father, Edmund Salmon, was very ill, and, according to Tom Croft—who was only five at the time but presumably got the story from his father--Edmund on his death bed made a deal with his youngest daughter and her husband. If the Crofts would engage to move into the house at 60 Richards Terrace, and if Mabel would promise to care for his ailing widow until she died, Edmund promised that Mabel would inherit the house. For Mabel, her father’s proposal was an opportunity not to be missed. Owning a home was a key rung up the middle-class ladder and one her family could never expect to make on Bob’s earnings as manager at a local petrol station. So, acting on a promise which was never put in writing, the Crofts moved into 60 Richards Terrace with Catherine after Edmund died.

For some years, the arrangement whereby the four Crofts lived in Mrs. Salmon’s house worked for everyone. The Richards Terrace house had three bedrooms, and with Mabel’s invalid mother ensconced in the front room downstairs, Bob and Mabel could have the front room upstairs and Esme and Tom each had a bedroom of their own. Bob had long wanted to own a racing greyhound and there was space in the yard at back for a kennel. Now that the family had a little more discretionary income, the Croft children were able to pursue their sporting interests after school—cricket and rugby and billiards for Tom, and tennis and amateur athletics for Esme. In the undemonstrative way of the Brits of their day, the four Crofts formed a tight, loving, supportive unit, and this was especially true after 1933 when Esme left school and went to work full time. It is at this point in the late 1930s, that the relationship with her daughter starts to structure my Nana’s life, so I shall detour for a moment to describe what my mother was like as a young woman., based on the diaries and letters I inherited from my parents.

Esme had made her parents proud by getting into Cardiff High School for Girls, the top high school in the city. She was a star on the hockey field and was obviously a bright girl with flashes of intellectual brilliance. Her Latin teacher was impressed by the way Esme Croft, who never bothered to learn the grammar, got top marks on the “Unseen’ part of the exam, easily figuring out the meaning of a piece of Latin prose she had never seen. But just as her mother had failed to master her times tables, so my mother at fifteen was failing in algebra, and, since a passing grade in every subject was then necessary to get the School Certificate, Esme and her parents decided that there was no point in her spending another year in school.

Dropping out of school in her mid-teens seemed rational at the time but it marked my mother for life. She was a competitive young woman and at fifteen she had met a bar that her elders judged too high for her to jump, and the failure stung. Later on, in the post-war years, opportunities for higher education for adults opened up but my mother was unable to take advantage of them because she lacked the basic qualification—the School Cert. One reason why our mother fought so hard for me and for Rose to stay on in school to the sixth form and try for university was because she wanted for us what she had been denied.

However, back in 1933, Esme Croft did not repine. She took a job in the accounts department of David Morgan’s, the big Cardiff department store, and made a success of it. She was quick with numbers and neat with the books, rarely called in sick, and was popular with superiors and co-workers alike. Part of her success was due to the fact that, while winning raises and bonuses, she was no one’s idea of a career woman. She spent her money on clothes, make-up, and hair, and, over the seven years of her life at David Morgan’s, the skinny, athletic schoolgirl metamorphosed into a slender young woman with a touch of the Katharine Hepburn about her. Her tiny 1939 diary details my mother’s busy social life and names the string of young men eager to take her to the pictures, pay for her drinks at the pub, and get her out on the dance floor. Unlike so many girls, one gathers, Esme did not fall into a sodden heap after a few Gins and she managed to be popular without being “fast.”

My mother Esme Croft aged about twenty This is one of several studio portraits she had taken of herself at this time. (Gill Collection).

Esme’s success at David Morgan’s and at the Young Conservative Club where she spent much of her leisure time were a source of increasing pleasure to her mother. Mabel Croft could see herself in her daughter almost literally, and as adult women, mother and daughter were allies.

Esme was good about chipping in her share of the family’s expenses, and if she had a cold or needed to wash her hair, she would grandma-sit and allow her mother to get out of the house to play some whist or spend a Saturday afternoon at the dog track with Bob and Jacko. When Esme’s young men came to call for her, they would sit down and chat with her mother, who was a good sport and liked a laugh. As Catherine Salmon’s infirmity progressed, keeping her daughter Mabel more and more confined to the home, my grandmother was able to both authorize and share in her daughter’s social whirl. As Esme moved into her twenties, Nana began to imagine how, someday soon, one of the nice young men from the Conservative Club would produce a ring and she would need to phone the vicar and the florist.

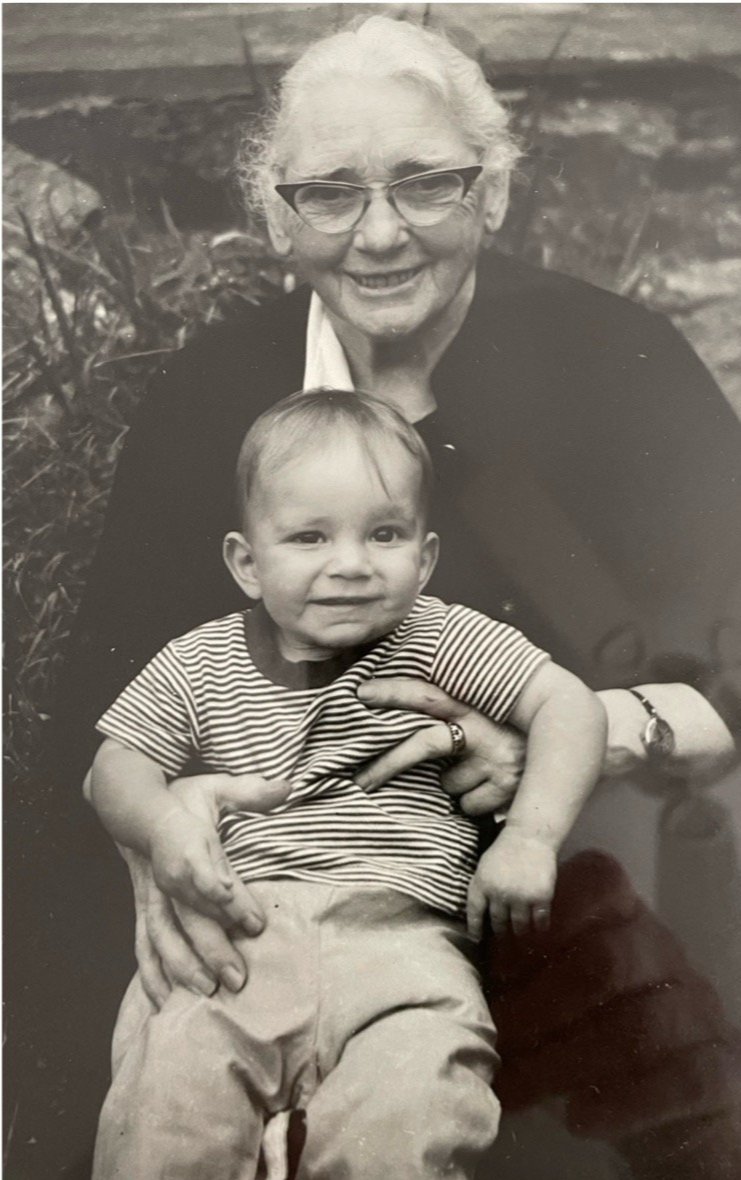

My grandmother and my mother, photographed at about age twenty. (Gill Collection).

The pleasure Mabel Croft took in seeing her daughter leading the kind of independent, fun-filled life she might have led in her youth if Catherine Salmon had not been her mother, was very needed. By 1939, it was clear to the Crofts that the price they were paying for 60 Richards Terrace was high. Mrs. Salmon was bedridden and insisted that she could never be left alone in the house for more than a few hours, and Tom Croft testifies that his grandmother was a nasty old woman who treated her daughter Mabel like a skivvy. He has a vivid memory of his mother kneeling on the floor to wash her mother’s feet and having her hair pulled till she cried.

And then, when she finally died in May 1939, Catherine Salmon had a mean trick to play on her daughter from beyond the grave. As we have seen, the Crofts believed that they had received a solemn from Mabel’s dying father that, if they moved into his house and looked after his widow until she died, Mabel would inherit 60 Richards Terrace. The Crofts had more than faithfully kept their side of the bargain but, in the days following Mrs. Salmon’s death, they learned that she had left her house and other property to be divided equally among her seven surviving children --Polly, Eddy, Edie, Ernie, Alan, May and Clem.

I judge Catherine Salmon harshly in this matter of the house, but it is not hard to understand how she came to be the nasty woman her grandson Tom remembers. She was, I was told as a child, an orphan, nothing has come down to us about her family or her early life, and without a place and date of birth and with a name as generic in Wales as Catherine Williams, genealogical research is likely to be fruitless. If Catherine was the child of an unmarried mother whose family abandoned her, she would have been put in an orphanage and then, as young as eleven, hardened and barely literate, sent into domestic service. How she came to meet the newly widowed Edmund Salmon is not known but marrying him was obviously the great turning point in her life. As Edmond’s wife, Catherine had commanded Edmund’s devotion, had his children, helped him steer the family through the loss of the inn, run a busy household, looked after her stepdaughter Emily as she succumbed to tuberculosis, and exercised authority over her own eight children. But, by the 1930s, with her Edmund dead, Mrs. Salmon was sad and old, bed-ridden and irrelevant. Lacking the resources to entertain herself, and bored almost—but not quite, not for eight years-- to death, she tyrannized the Crofts.

As I read her, Catherine Salmon had no special love for her daughter Mabel and probably disapproved of her son-in-law Bob who spent his nights at the club and his weekends at the races. It did not escape her that Bob kept as far away from her as possible and that her Croft grandchildren resented the way she treated their mother. As Catherine Salmon saw it, she had been given care but not love in exchange for her house, and May was merely fulfilling a Christian daughter’s duty. As she lay in bed awaiting death, Catherine relished the power she still had over her family and saw a legal way to show the world that her favor could not be bought.

Within a day of Mrs. Salmon’s death, a fight broke out among her children over her estate, and Tom Croft, who was fifteen at the time, still had vivid memories of that fight in 2022. Bob Croft was close to his son and, hemmed in by his wife’s rapacious and ungrateful siblings found a willing listener in his son, passing on a sense of grievance over inheritance that Tom never lost. In contrast, my mother in her 1939 diary does not even mention her grandmother’s death and says nothing about the family infighting. Esme’s only allusion to this important moment in her family’s life is to say that she and her mother had had a fight because she—Esme--refused to buy a black outfit for the funeral. Money was not the problem here--Esme loved to shop for clothes—but I think my mother was making a statement here. By wearing her old navy suit, she was telling the world that she at least was not pretending to mourn.

The fight over 60 Richards Terrace which made such an impression on Tom Croft and so little on his sister, seems almost comical now. Each Salmon child stood to inherit perhaps seventy pounds plus a piece of furniture and some crockery, but to some of them that was well worth fighting for. Edie and her family seem always to have been even less affluent than the Crofts, so she fought hard for her cut. To Clem, a blind man with a blind wife and one blind child, struggling to survive on disability, seventy pounds was a lifeline. But the stakes were highest for Mabel and Bob. They had never managed to save more than a few pounds and they stood to lose their family home and become renters again. But Mabel Croft was not the steely Catherine Salmon’s daughter for nothing, and she came up with a solution. Somehow, even while tied to her mother’s apron strings, Mabel had managed also to be of help to an older woman friend in bad health. In the midst of organizing the funeral, fighting with her brother Ernie over the sideboard, and arguing with her daughter about wearing black, Mabel went over to see this friend who agreed to loan her three hundred ponds to buy out her siblings. By the fall of 1939, the precious deed to her parents’ home was in Mabel Croft’s name, and, even as Britain lurched into war with Nazi Germany, she had the satisfaction of knowing that she and her family at least had a good roof over their heads.

And then something happened that would fundamentally change Mabel Croft’s domestic landscape and shape her personal experience of the war. Her daughter Esme fell madly in love, and it was not with a member of the Young Conservative Club.

5. Mabel and Esme—and Bill!

It is odd to read my mother’s diary of 1939. She and her Young Conservative Club friends were enthusiastically political and yet, by her account, when it came to the news from Europe, they kept their heads in the sand. As the summer of 1939 passed, my mother kept penciling in the boyfriends, the pub evenings, the club debates, the movies showing at the Capitol, but she also she lets drop that she is writing cheery little notes to friends who had been called up. It was a very strange moment and, given the overwhelming international forces at work, maybe plating the ostrich was the smart move. Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we…???

And even as the shadow of war began to darken Esme Croft’s skies, the name “Bill” pops up in the diary and soon blots everything else out. This Bill is, evidently, a smooth operator. When he takes Esme to the pictures, he not only buys tickets for the expensive seats upstairs but presents her with a pound box of Black Magic, her favorite chocolates. And with tantalizing details like this, my mother’s diary ends, and what I consider one of the great love stories of the twentieth century—the marriage of my parents-- begins.

Bill and Esme met by chance. At one of the Young Conservative Club parties in September 1939, a rather silent young man appeared called William Scobie. He was a third mate on the merchant ship Umberleigh, on leave in his home port of Cardiff while his vessel had its hull scoured and its holds filled. Bill, as he was known, was a committed socialist but his brother Stewart and his Clode cousins were Conservatives, and they dragged him along, claiming the Tories always threw the best parties, with lots of beer on tap. Bill Scobie was fond of beer, and, armed with his first pint, he looked around and, according to family legend, saw a very attractive young woman run up to a wall and do a handstand. “Who is that girl,” Bill asked his cousin, who replied it was Esme Croft, the club secretary and social dynamo, and offered to introduce him.

I like to picture my parents at this moment in their lives.

Bill Scobie, aged about 25, and Esme Croft, aged about 21. (Gill Collection)

It was very much a case of opposites attracting. Their political views (Tory vs. Labour) clashed and always would, their social backgrounds differed, he was a good drinker but a terrible dancer. None of it mattered. In her elegant evening frock, slender, lithe, graceful, energetic, fizzing with fun, she looked to him like Cardiff’s answer to Barbara Stanwyck. Quiet yet assured, tall and broad-shouldered in his naval uniform, his hands and face bronzed from salt and wind, he was every girl’s idea of a Prince Charming. From this point on, he would always be “My Bill” and he never looked at another woman.

In the fall of 1939, Bill Scobie did not let the grass grow. Unlike Esme’s young Tory friends, he did not have his head in the sand, saw the war coming, and grasped what this would mean for him as a merchant seaman. After nine years at sea, with all the social and sexual opportunities the seaman’s life afforded, Bill Scobie knew what he wanted was a wife and perhaps a family and understood he had no time to lose. By the end of his leave, he and Esme Croft were madly in love and the “cold war” between Britain and Germany was coming to an end. Thus, when the cable came in February 194o to tell her that her Bill would have a few days of shore leave in Cardiff, Esme had a vicar, a church, a reception, a wedding outfit, a bouquet, a cake, and two nights in a hotel lined up. Almost within hours of disembarking, Bill found himself on the steps of St Margaret’s church, a married man.

The group photograph of my parents’ wedding at St Margaret’s church in February 1940. Nana and Bob stand at the bride’s left. Her maid of honor is her first cousin, Renee Clemo. The unidentified man next to the groom is a stand-in best man for Bill’s brother Stewart Scobie, an infantryman in France. Vera Pepler, Stewart’s then fiancé, later wife, is the woman on the far right. The woman standing behind the groom is Rose Torresen, Nana’s neighbor and friend. Evelyn Scobie, Bill’s mother, was probably too ill to attend. I am not sure why Esme’s brother Tom is not in the picture. It is possible he could not get leave at short notice from his job in the armaments factory.

Three days later Bill was back at sea, headed for Narvik in Norway where his ship just managed to sneak past the German ships carrying the troops for the Nazi invasion and occupation of Norway, but that hotel room had not been money wasted. Over the next four years, Esme and Bill Scobie counted their time together in hours rather than days but sexual chemistry at once became passion and fidelity, and in the almost daily letters they exchanged, one big message came over loud and clear. I love you, I miss you, my body aches for yours, I live for the moment when we are together again, I live in terror that that moment may never come. Throughout my father’s life at sea, words on paper would keep the bond between my parents from breaking, and an ability to put love into words was one of the things my mother taught my father.

For the next four years, my father lived in danger and my mother lived in dread. In his letters, Bill could say nothing much about where he was or what his ship was carrying, but there was no escaping the fact that he was doing convoys. A convoy consisted of a line of disparate and heavily loaded merchant ships, sometimes carrying troops and armaments but more often continuing the routine trade on which the warring island nation depended for its survival. The convoys were escorted by any Royal Navy vessel that could be spared, and they were under regular attack from German submarines that, by the end of 1940, had become experts with the torpedo. As my father recounts in his wartime reminiscences, there was one day out in the Atlantic when a U-boat torpedoed the ship behind his and then the ship in front, then eight more, and he fully expected to be next to go down. Even in port, the life of a junior officer in the Merchant Navy could have its moments.

Early one morning in the port of Alexandria in Egypt, newly promoted Second Mate Bill Scobie heard a mighty crash and rushed up on deck in his pajamas. The Umberleigh was being loaded with ammunition, and a sling full of detonators had been dropped into the hold by accident by local dockworkers--who then ran away from the ship as fast as they could. A dozen small fires had already broken out in the ship’s hold. “Get down below, Bill,” said the First Mate, “I’ll send down the fire extinguishers,” and down into the hold Bill went and put the fires out. It was the closest my father came to death and, when he remembered going down into that hold, my father writes that he still broke out in a cold sweat.

But if Esme lived in dread of the fateful telegram announcing the sinking of the Umberleigh with all hands, her parents and her brother could probably have received the news of Bill Scobie’s death with resignation bordering on relief. The lightning courtship between Esme and Bill had given the Crofts very little opportunity to get to know their new family member, but it was clear that he was not like the light-hearted young men who had clustered around Esme in the pre-war years. More importantly he was not like Bob or Tom. He could certainly take his beer and was a sound fellow to have with you in a bar brawl. He could steer a ship and pull an oar and even swim. But he played no team sports and he placed no bets and he was a member of the Labour party.

Mabel Croft in particular was less than thrilled with her new son-in-law. Obviously, this young Scobie was a fine, serious, trustworthy young man, and his widowed mother Mrs. Evelyn Gilbert Scobie, whom Esme had met a few months before her death, had been a respectable person.

This very bad snapshot, taken I believe at the end of 1939 on board the Northleigh, shows my father and a crew mate and, in the background, his mother Evelyn Scobie. This is the only photo I have of my paternal grandmother who died in April 1940. Only a short time before his own death, my uncle Stewart told me the story of how, as an infantry man in the British expeditionary force trapped at Dunkirk by the German army, he had received a cable from his brother Bill informing him that their mother had died. Stewart said that he had walked away to try and compose himself for a few minutes, and then returned to the men of his regiment. They were all facing death so there was no time to mourn. As it turned out, Stewart Scobie was one of the lucky men snatched off the beaches in the famous Dunkirk retreat, and he would serve out the war with distinction. Stories like this explain why the men and women of my parents’ generation remember World War II with passionate nostalgia. It was the time they were most challenged and felt most alive.

But the roots of both the Scobie and Gilbert families lay in Grangetown, the area around the Cardiff docks, and that fact set off warning bells in the mind of Esme’s mother. Mabel Croft was not sure of the exact location of the Cardiff dockland but in Roath it was known as Tiger Bay, a place where persons of different nations, languages, and skin tones were said to walk the streets and sin and depravity lurked. The rumor had reached Mabel that Bill’s maternal grandmother had kept a sailors’ boarding house right on the docks, which sounded very unsavory. All in all, the best things about her new son-in-law in my Nana’s eyes were that he supported his new wife generously and that for at least eleven of the twelve months he was away at sea.

That still left Mabel with a daughter le hunched over the radio, desperate for shipping news, rushing for the mail as it fell onto the mat, and writing letter after letter on thin blue airmail letter forms. Esme had always been volatile and quick-tongued, but now, with all the strength of her passionate nature focused on her new husband far away, she was becoming impossible to live with—and this at a time when the war was going so very, very badly.

In 1940, Cardiff—a port city with an important armaments factory where sixteen-year-old Tom Croft now worked—was heavily bombed, and houses at the end of Richards Terrace were destroyed. Following that bombing raid, the Croft family was evacuated to the safety of Cowbridge, then a bucolic village some ten miles away, but they did not stay there long. They were born and bred city dwellers who found gardening a chore not a pleasure, never took a walk just for the fun of it and had never wasted money on a picnic basket and a primus stove. In Cowbridge there was of course a pub or two but no local cinema, and no commercial district like Broadway just down the end of Richards Terrace. Bus service from Cowbridge was unreliable and Bob and Tom often bicycled to work but for Mabel, who did not bike, at home all day with nothing much to do and no neighbors to chat with or siblings to quarrel with, Cowbridge was Outer Mongolia with a mildewy cottage instead of a yurt. Within months of the bombing, the Crofts had an air raid shelter put up in the back yard and they all moved home to Richards Terrace. Better bombs than cows!

It is not clear how many shore leaves my father had between his wedding and my birth in 1942, but it seems fairly clear that over that year, my mother lived with her negligee packed and a railway timetable to hand. When Bill’s ship docked in a distant port, Esme was waiting on the dock for his ship to anchor, ready to leap into bed as soon as she got on board. In Bill’s tiny cabin, sound-proofed in iron, and surrounded by curious but unobtrusive crewmates, the two young Scobies found privacy and bliss. But things were different if Bill’s ship docked in his home port, Cardiff. There, he was expected at his mother-in-law’s house and he and his wife had little time alone during the day and no privacy at night. In Cardiff, Esme’s tense but tight bond with her mother became an inescapable factor in her marriage and would remain so until her mother’s death. From the beginning, my father found himself competing for my mother’s allegiance, and during the war years Nana had the upper hand since she and Esme were joined at the hip.

Given the heat that flamed up each time my parents were alone together and their reliance on withdrawal for birth control, a slip up was almost inevitable. When, at the end of 1941, her daughter Esme announced that she was pregnant, my grandmother was furious—and not irrationally. The war was going from bad to worse, with Hitler’s forces gaining ground on every front and bombs raining down on British cities. There was often a shortage of foods and basic household goods, and the Croft family relied on Esme, who had been obliged to give up her job when she married, to stand in one line after the other, the family ration books in hand. Now there would be a baby to care for and fear for, and a new mouth to feed, and my grandmother was at her wit’s end to put something resembling food on the table three times a day. She fiercely railed against Bill Scobie for yielding to passion and getting his wife knocked up at the worst possible moment.

Me at about six months. The mark left on my lip and the rash on my right hand are apparent. The rash faded as I grew older but, when I visit a new dentist, I am still questioned about the growth on my upper lip. (Gill Collection)

But all this acrimony was put aside when, on June 12, 1942, I was born in my grandparents’ bedroom at 60 Richards Terrace and immediately wrapped in a blanket of love and care. My first weeks were difficult as I was born with two forms of nevus--a large, disfiguring growth on the middle of my upper lip and a purple-red rash on my right hand and forearm. The family doctor recommended the growth on the outside of the lip be excised immediately, and this made it hard for me to suck. Once i had got over that hurdle, however, I thrived and became a source of great joy, especially for my grandmother who had helped both me and my mother through those testing early weeks.

All the same, following my arrival, the tensions underlying the relationship among my father, my mother, and my grandmother ratcheted up. Now, if my mother wanted to join my father on shore leave in a distant port, she needed her mother to look after me. And, if my father came into the port of Cardiff, either my parents had to sleep with me in the room or I had to be moved into my grandparents’ bedroom. All these sleeping arrangements got more difficult, of course, in 1946 when my sister arrived and both she and I had to be moved out of our mother’s bedroom when our father came “home” These arrangements were successfully negotiated between my mother and my Nana, but it was clear to my father, a very honorable and thoughtful man, that he was racking up a debt of gratitude to his mother-in-law that would have to be repaid.

6. Life at # 60 Richards Terrace 1942-1947

Despite the terrors and privations of the war, this was I think, the great period in my grandmother’s life. She had all her family in the house she owned, and, with my father away at sea most of the time, she, like her mother, before her, ruled the roost. A big part of Nana’s happiness revolved around me, who in those years was more Croft than Scobie, so this now becomes very much the story of my grandmother as I knew her.

So, into what kind of world did I come into consciousness. We Crofts lived, as a I have said earlier, in Roath, a solidly lower-middle-class area of Cardiff that, as I remember it, suffered mainly from its contiguity on one side—our side--with a low-class neighborhood with the unfortunate name of Splott. We Crofts shopped in Splott every day and usually went to the Splott Cinema since it was an easy walk. Nana’s sister Auntie Edie, whom I knew very well, lived, I think, in Splott, but I can’t be sure as I was never taken to her house or indeed the house of her daughter Dottie who had managed to move “up” to a house on Richards Terrace. As I said earlier, Aunty Edie was one of the relatives we Crofts condescended to.

In recent years, multigenerational households like we Crofts at Richards Terrace have become more common in middle class America, but my grandchildren would have difficulty recognizing my birth home as middle class. My grandparents, my mother, my uncle Tom, and, after her birth in October 1946, my little sister Rosie and I lived very much one on top of another in a way more familiar to recent immigrants to the USA than to citizens of long standing. As I found when I moved to the Boston area in 1967, space is one of the great American luxuries. In the U.S., I discovered with delight, there was room to throw one’s arms wide without knocking something over, room between beds for two sisters to get out of bed at the same time, room in the street to walk without constantly jostling and dodging.

I took this photograph of 60 Richards Terrace in 2021. The outside of the house is essentially unchanged since my childhood. (Gill Collection)

In recent years, multigenerational households like we Crofts at Richards Terrace have become more common in middle class America, but my grandchildren would have difficulty recognizing my birth home as middle class. My grandparents, my mother, my uncle Tom, and, after her birth in October 1946, my little sister Rosie and I lived very much one on top of another in a way more familiar to recent immigrants to the USA than to citizens of long standing. As I found when I moved to the Boston area in 1967, space is one of the great American luxuries. In the U.S., I discovered with delight, there was room to throw one’s arms wide without knocking something over, room between beds for two sisters to get out of bed at the same time, room in the street to walk without constantly jostling and dodging.

According to my uncle Tom, the ground floor at 60 Richards Terrace front to back had a front room, a middle room, a kitchen-scullery, and a loo. The scullery, which opened onto the back yard, was where the food was cooked and the dishes were washed and dried. The middle room was where the family ate and spent most of the day. With its dining table and chairs, an armchair for Bob close to the fire, a sideboard for dishes and cutlery, and a side table for the radio, you would have had trouble swinging the proverbial cat in that room and indeed, compared with the rooms in my current unremarkable 1950s suburban American Colonial, all the rooms at Richards Terrace were small. The big front bedroom could fit a double bed, a wardrobe, and a dressing table, and the small bedrooms had room for a single bed and a dresser or a crib and not much else. Furthermore, we Crofts did not have certain amenities American suburbanites today take for granted--a basement, an attic, a garage, a breezeway. We didn’t even have a front yard since the front room window was maybe ten feet of paving and a low rail from the sidewalk. Out back, there was a mainly paved yard with a coal cellar from which coal was brought up in the coal scuttle to feed the fire, a dog kennel before the war, a bomb shelter during the war, and maybe a toolshed. As for a patio with maybe a tree where you could put a table and chairs and welcome friends for drinks of a sunny evening –that was something the rising middle class of Roath had yet to even dream of.

Yet, if the house on Richards Terrace looks small to me now, it felt spacious to the Crofts who had recently been afforded the luxury of a front room. Until May 1939, the front room of the house, as we have seen, had been the bedroom of the owner, Nana’s mother, Catharine Williams Salmon. It was the biggest room in the house, and, after my parents married in 1940 and after my birth in June 1942, you might assume that it would have become my mother’s bedroom where she and my father would have some space and privacy when he came back to Cardiff on one of his precious leaves--but that was not what happened. Instead, Nana got to enjoy that symbol of middle-class respectability, a proper front room, and the only person who might have objected was my father, and he had no say in his mother-in-law’s house. The front room, or lounge as our family was learning to call it, now held the “good” suite and Grandma Salmon’s sideboard, now sadly marred by German shrapnel. Nana kept her front room furniture dusted and polished and the carpet swept with dustpan and brush. A Hoover, the British vacuum cleaner, was a luxury the family would acquire after the war, but still use sparingly. Had dust been allowed to collect in that room at #60 it would not have greatly mattered. The front room was meant for visitors not inhabitants though visitors were infrequent and actually felt happier in the middle room, which had a fire lit and was close to the tea kettle.

As far as I can reconstruct the daily routine in the Richards Terrace war years, the five members of the Croft family could most often be found assembled at mealtimes. Around 8 a.m. they came downstairs from the bathroom one at a time for a breakfast of tea and porridge or toast with marmalade and “marg” since butter rations were tiny. Everyone came home for “dinner”, the main meal of the day, served promptly at one and featuring meat, potatoes, and veg (usually cabbage), the canonic fish on Fridays, plus biscuits (cookies) and tea. Before scattering in the evening, we Crofts sat down to “tea” at five, with “buttered” bread and jam or potted meat paste, canned fruit or the drearily ubiquitous stewed rhubarb dowsed with evaporated milk. Maybe on a Saturday, a small salad might appear, consisting of a slice of ham or tongue or corned beef, a slice or two of cucumber, a wedge of tomato, a lettuce leaf, and, if available, a dollop of Heinz salad cream, all washed down of course with tea. Our family was intent on moving up the social ladder, but we had yet to realize that the very names we used to refer to meals relegated us to the provincial lower classes.

Despite all the people living there, the house at Richards Terrace was a cold, damp place since the only sources of heat were the kitchen range and the small coal fire in the living room. I was never warm all over all day until I emigrated to the USA and discovered central heating. On the other hand, the emotional heat in the household was high because, as you can see, there was very little privacy. If someone was stuck at home but wanted to get away from the others without going out, their only refuge was the yard, pitch black during the war, or a small, chilly bedroom lit by a central bulb in the ceiling. Throughout my youth, people did a lot of their reading in bed to keep warm, and, with bedside tables and lamps still a rarity, they had to leap out of bed to put out the light when ready to sleep. Until I went to college, I did my homework and read books in bed, and there was no space between my bed and Rose’s to put a lamp had we owned one. One of our father’s loving habits was to come along to our bedroom after we had fallen asleep and switch off the light.

If the house was cold, the women in the house sent the emotional thermometer soaring. As I can testify, my mother was always voluble and volatile, and during the war, forced by marriage and motherhood to give up her companionable job at the department store, her temper was on a hair trigger. Esme lived in daily expectation of some boy cycling up to the house with a telegram notifying her that her Bill’s ship had been torpedoed and gone down with all hands. As for Nana, I can equally testify, she was stubborn, opinionated, and passive-aggressive. Those two women were like a stick of dynamite next to a non-safety match, and the resident males, Bob and Tommy, got out of the way as much as possible. Tom Croft was already a man at fifteen when he left school to work at the nearby Royal Ordnance factory. He and his father were out all day at work, and in the evenings, they usually repaired to their various clubs and favorite pubs. The Croft men came home mainly to sleep and eat, happy to earn the money while leaving the women to cook and shop and clean and read and listen to the BBC news and look after little Gilly and fight it out.

My mother’s letters to my father at the time of my sister’s birth in October 1946 offer a hint that a pattern of separation between males and females operated in the microcosm of 60 Richards Terrace. Esme Scobie gave birth to all her three children at home, and, when my sister Rosemary finally decided to make her entrance three weeks overdue, my mother was once again moved into her parents’ big front bedroom to deliver her baby. She then settled in for the ritual two weeks (!!!) of bedrest, her mother in constant attendance. In her daily or twice daily letters to her faraway husband, my mother tells of the daily (!!!) visits she received from the family doctor or the district nurse. She tells of female friends who drop in to coo over the large and beautiful newborn and admire the proud mother’s gorgeous new knitted bed jacket. But in all the dozens of pages she devotes to her long, tedious days in bed, my mother never once mentions her father or her brother stopping by to chat with her and have a look at the baby. The front bedroom had seemingly metamorphosed into a female space into which only that demi-god THE DOCTOR had admittance.

Of my years in Richards Terrace, I remember almost nothing. I remember mastering the up and down finger movements for Intsy Wintsy spider and feeling very proud of myself. I must have been quite small then. I remember the tiny “Flower Fairies of the Wayside” books I was given after I learned to read and which I adored even though I could at most tell a daisy from a dandelion. Three anecdotes of my early years were passed down to me as part of the family lore. My mother was out shopping one day in the middle years of the war when food was severely rationed, and she put the family’s precious five eggs in the pram with me. Turning her back for a moment, she looked around to find that I had smashed the eggs and was happily spreading goo over the pram and myself. Disaster! On the same note of wartime privation, when given my very first banana, I reportedly spat it out. I still do not care much for bananas. Last but not least, as a huge treat, I was taken to the “pictures” to see “The Wizard of Oz” but had to be carried out early in the movie screaming with anguish, “Trees don’t talk, trees don’t talk.”

I have a couple of memories of my own, not calcified and changed by multiple narrations, and I have narrated one in my “Bob” chapter. The other concerns the lady next door, my grandmother’s friend Mrs. Rose Torresen. A special treat for me was to be invited next door for tea with this widowed lady. She served me her homemade junket which I found unutterably delicious. Milk puddings and custards are still among my comfort foods. And in Mrs. Torresen’s front yard was a Maytree—a hawthorn tree that in spring had pink blossom. I think that tree has stuck in my memory because, in that sooty, war-weary world I was trundled through in my pram and my pushchair, it was the first beautiful piece of nature I ever saw. The Japanese have their cherry trees. Proust had his aubepines. I had Rose Torresen’s May tree.

Rosie and I sitting outside our grandmother’s scullery at the back of Richards Terrace. We are wearing the rag “wiggers” Nana put in to curl our hair and we are pretending to smoke candy cigarettes. (Gill Collection)

So, what was my life like during those years when I was a Croft, not a Scobie? Well, the key thing to know is that I was lucky enough to have two mothers. More precisely, my mother and my grandmother merged for me, and, later, for me and Rosie, into a single maternal figure. Let me be clear. Esme Scobie was a more-than-good-enough-mother (to cite Winnicott), but our absent father was the focus of her emotional life. Mummy and the Daddy we rarely saw and barely knew kept in touch by letter every day, sometimes twice a day. Mummy lived with one ear cocked for the ring of the doorbell signaling the arrival of Daddy’s telegram saying where and when his ship was due into port. She would then take the first train out of Cardiff General and be gone for maybe a week, and Rose and I would watch her leave without a tear and then barely notice her absence.

When my mother did the three-month voyage on Daddy’s ship, all I remember is wishing I didn’t have school so I could go too as being on the Northleigh was my idea of heaven. Our mother was the bedrock under us, but Rosie and I did not miss her when she went away because nothing in our daily lives changed. We were used to our Mummy being gone, knowing she always came back, and we had Our Nana. She never went anywhere, and she had Bob and our uncle Tommy to back her up, so Rosie and I could be secure, untroubled, content, a bit bored, but cocooned in love and care.

And, what did Nana and I do in those early years? Not a lot by the standards of today. Basically, since I was a little chatterbox from age two, we talked. I would tell her about my day at school, during which nothing much happened, and she would tell me about her day at home, during which nothing much happened. Every now and then she would share tidbits about her childhood, which I stored away because her parents and her family were so different from my own.

Nana, Rosie, and I, snapped in front of the bay window at 60 Richards Terrace, all wearing our fancy hats. In the picture, I look to be about seven and Rosie about three. (Gill Collection)

I was a passionate reader from age four, so Nana and I spent a lot of our hours together reading. Our family owned only a handful of books, but print was one luxury we could not do without. Mummy went to the library at least once a week and we pretty indiscriminatingly devoured all the books she took out. I also had a subscription to a lot of comics—I took “Dandy” and “Beano”, “Girls Crystal” and “Girls Own Magazine” --while Nana had her Tory newspapers--the Daily Express, Reynolds, and the Daily Telegraph--several local papers like the South Wales Echo, plus the Daily Mirror, which was Labour but she liked to do the daily crossword.

When I began to tune into the world around 1948, Great Britain was pretty much a media desert. There were movies of course and we went regularly to the cinema, sometimes down to the Capitol and the Empire in the center of Cardiff, but more often to the Splott Cinema which was just a walk from our house. When my uncle Tom was courting my auntie Joan, they were sometimes persuaded to take me with them to the Splott and I gave them no trouble. Perched on top of a fold-up seat, a bottle of pop or a package of crisps barely touched in one hand, I sat still and silent, entranced, absorbed in the movie. The moment when Betty Grable stepped out of her portrait on the wall is with me still. Magic had entered my life. The only time I made a fuss for Tom and Joan was when I got very excited once and got swallowed up by the seat.

As homes at that period had no television and no commercial radio stations, and our family, who did not much care for music, owned no gramophone and no records. What we had was BBC radio, with its, I believe, three programs, and in our house the wireless, as we called it, was on all day until the programming ended at ten with the National Anthem. What we listened to was talk—the news, Woman’s Hour, Children’s Hour, Desert Island Disks, comedy shows, radio-novellas like “The Archers”. If orchestral music came on, Nana would change the program, but she liked musicals and pop songs and the two of us would sing along. By the time I was five I had a big repertoire of nursery rimes and was ready to pick up songs from the two World Wars--“It’s A Long Way to Tipperary”, “Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kitbag”, “We’ll Meet Again”—and music hall songs from Nana’s youth—"Daisy, Daisy”, “Don’t Dilly Dally on the Way”, “Burlington Bertie”, “Your Baby Has Gone Down the Plughole”. I can still croak those old songs today.

For the wedding of our uncle Tom and auntie Joan in March 1951, Rosie and I were two of the three bridesmaids, and Nana crafted starched-net, Dutch-style caps for us which were much admired.

Throughout my childhood, it was to Nana that I turned when I had a problem, and that problem was often with sewing. Needlework was then a regular part of the curriculum for girls, and, from the age of five to fourteen, it was my bete noire. Not only did sewing bore me but I was disastrously bad at it—which made me hate it more because I hate to fail at anything.

Needlework reared its ugly head in my first term at Our Lady’s Convent School where the nuns had decreed we five-year-olds should learn to smock. We had to bring in from home a piece of fabric with lines of dots ironed onto it. We then had to tack long, regular stitches along the dots, pull the fabric into neat folds, and then embroider lines of smocking. My granddaughters, who have clever fingers and love handicrafts. would have aced smocking, but it was completely beyond me, and I was in despair. My mother had no time for me and my needlework, but Nana was patient and tried to show me what to d but in the end she took the grubby, tear-stained, nightmarish bit of pink fabric that I can see in my mind’s eye to this day and did the smocking for me. You can see why I loved my Nana.

The wedding party of my aunt and uncle outside the porch of St Margaret’s church. (Gill Collection)

7. A Move Down the Hill. 1948-1958

Following his promotion in 1944 to captain of the Northleigh, my father was earning a handsome salary and was in a position to get a mortgage on a house of his own, but he was unable to persuade his wife to move out of her parents’ home. Esme got on very well with her father and brother, and though she and Nana were forever sniping at one another, they shared housework and childcare so Esme, who had little taste for domesticity, had time for books and crosswords and writing long letters every day to Bill. And of course, whenever the Northleigh docked in any port but Cardiff, Esme could leave one or both of her children with her mother and be off for another romantic and increasingly ritzy rendezvous.

In, I think, 1947, Esme persuaded her mother to look after me and Rosie while she with did a three-month voyage on the Northleigh to Canada. It was by far the longest time Bill and Esme had ever had together, and I think it was then that they decided that they could no longer bear the separations. They agreed to build up their savings so that in a few years Bill could afford to leave the sea and study for the qualifying exams that with luck would open up a new career on land. But, in the interim, my father was on the look-out for a solution to his marital problems, and in 1948 he found it.

Two new brick buildings, each building consisting of two flats, one atop the other, were going up on the bomb site at the corner of Richards Terrace, and Dad proposed the Croft-Scobie menage should purchase and move into two of the flats. Nana and Bob could have the bottom flat, while we Scobies occupied the top flat which was inconveniently accessed only by an external cement staircase. This move would be possible if Nana sold 60 Richards Terrace.

232 Newport Road in 2021, essentially unchanged from my youth. The upstairs window mid-frame was once Rosie and my bedroom window. The window to the right was in our kitchen. I took this photo to show the stone wall which served me as a jungle gym. I would move over the top of the wall in a low crouch, accelerating when I went by the window to my grandmother’s kitchen. I was strictly forbidden to climb this wall as well as the brick wall that separated our property from the neighbor’s, along which I would actually run. It was on this brick wall that I used to meet up with my best friend, the boy next door, Michael Haas, pronounced Hayes. He and I never went into each other’s houses and our parents had no social contact. My guess is that this was because the Haases were German Jews.(Gill Collection)

Exactly what the financial arrangements my father proposed to my grandparents are not documented, and I have no good understanding of how a first-time buyer purchased a home in 1948. My assumption is that my father was in a position to swing a mortgage for both flats and had always supported his wife and family through increasing contributions to the Croft-Scobie household income. But my parents were saving hard to enable Bill to leave the sea so Bill asked Nana to provide the down payment for both units and, for that, Nana, who had never been able to save much, would have to sell her house. As we shall see that lack of clarity over how much money Nana invested in 232 Newport Road and what expenses my father incurred during the joint tenure of the house would provoke a family feud many years later.

Persuading Mabel Croft to sell her house and move could not have been easy. She was a stubborn woman, set in her ways, averse to change. The house was her only real asset and she had emotional capital in it that outweighed the modest equity accrued. It was her mother’s house, she had fought for its ownership with her siblings Ernie and Edie and Clam, and she had happily reigned over it for some nine years. In the end, I suspect that for once Bob put in his oar and sided with his son-in-law. Bob was a peace-loving man, he had a good head for figures, and he could see the two-flat solution was a win-win for everyone.