Mike, Marriage, and Motherhood

Labour Pains

“This piece has an unexpected and undesired relevance in 2024 amid the urgent debate on pregnancy, miscarriage, and abortion that has followed the Supreme Court’s Dobb, decision, overturning Roe v Wade.

In my reproductive history, I count myself a very lucky woman. I wanted children, as did my husband, and I got pregnant easily. I had three healthy, full-term pregnancies, and gave birth to three healthy babies. But, as I recount below, having babies even for the privileged like me is not for wimps. Those three normal, successful pregnancies taxed my mind and my body more than anything I had anticipated or have experienced since, and the motherhood I embrace with such ardor has come with its own special sorrow.

The piece was written in 1972 soon after the death of Sarah, my second child. The rambling, illogical progression reflects my state of mind at the time.

Sarah, almost nine months old, was on a camping holiday with her father Mike Gill, her four-year-old brother Chris, our Dutch friend Wilhelmina Dowell, Wil’s two young boys Ian and Gavin, and her younger sister Marianne, who was visiting from the Netherlands and whom we employed as our babysitter.

While this combined Gill/Dowell party drove South in search of sun and beaches, I holed up at home in Whitman Hall, the Radcliffe College dorm where Mike and I were house parents. I was on deadline to finish the rewrite of my Ph.D. thesis for Cambridge University, and the plan was for Mike and Wil and Marianne to take all the kids away so that I could write without distraction.

Those were the days before cell phones and Mike and I were not much into daily phone calls anyway, so I was sitting eating lunch in the dorm cafeteria, my mind busy with existentialism and narrative technique, when Chris Dowell, Wil’s husband, called me to the phone. It was Mike from, I think, South Carolina, phoning to tell me that our baby was dead. Somehow, he and Marianne had had a miscommunication, and everyone had gone off in different directions to explore, leaving Sarah asleep in the tent. When someone got back—I never got details about any of this—they found that the tent had blown down in heavy wind and Sarah had suffocated.

Mike was sobbing with grief and guilt over the phone, and I was, I suppose, in shock but I found the right thing to say. I told Mike that I did not blame him, which was and would always be true, that accidents happen, and that we would have another child.

Work, I find, is a good resource when you mourn, so I completed my thesis that spring, and by the end of 1972, at the age of thirty, I could at last style myself Doctor Gill. It was a proud and bitter achievement, and Mike and I only really began to live again when, after two early miscarriages, I brought Catherine safely into the world on Friday, April 13, 1973—my lucky day ever since.

As all who know me know, writing—letters, email, and, nowadays, text—is how I communicate. I will talk a blue streak when someone manages to get through to me, but when I had a land line I rarely picked up and today my cell phone is never in my hand and rarely in my pocket. Much of this is due to the fact that social confidence was carefully bred out of me in my childhood, and deep inside me lurks the perception that people will not be happy to hear from me. But above all, I think, the phone is associated for me with trauma. News of the deaths of people I loved very much—Sarah’s in 1971, Mike’s and my mother’s in 1990, my sister Rose’s in 2004 — all came to me out of the blue when I unthinkingly picked up a phone.”

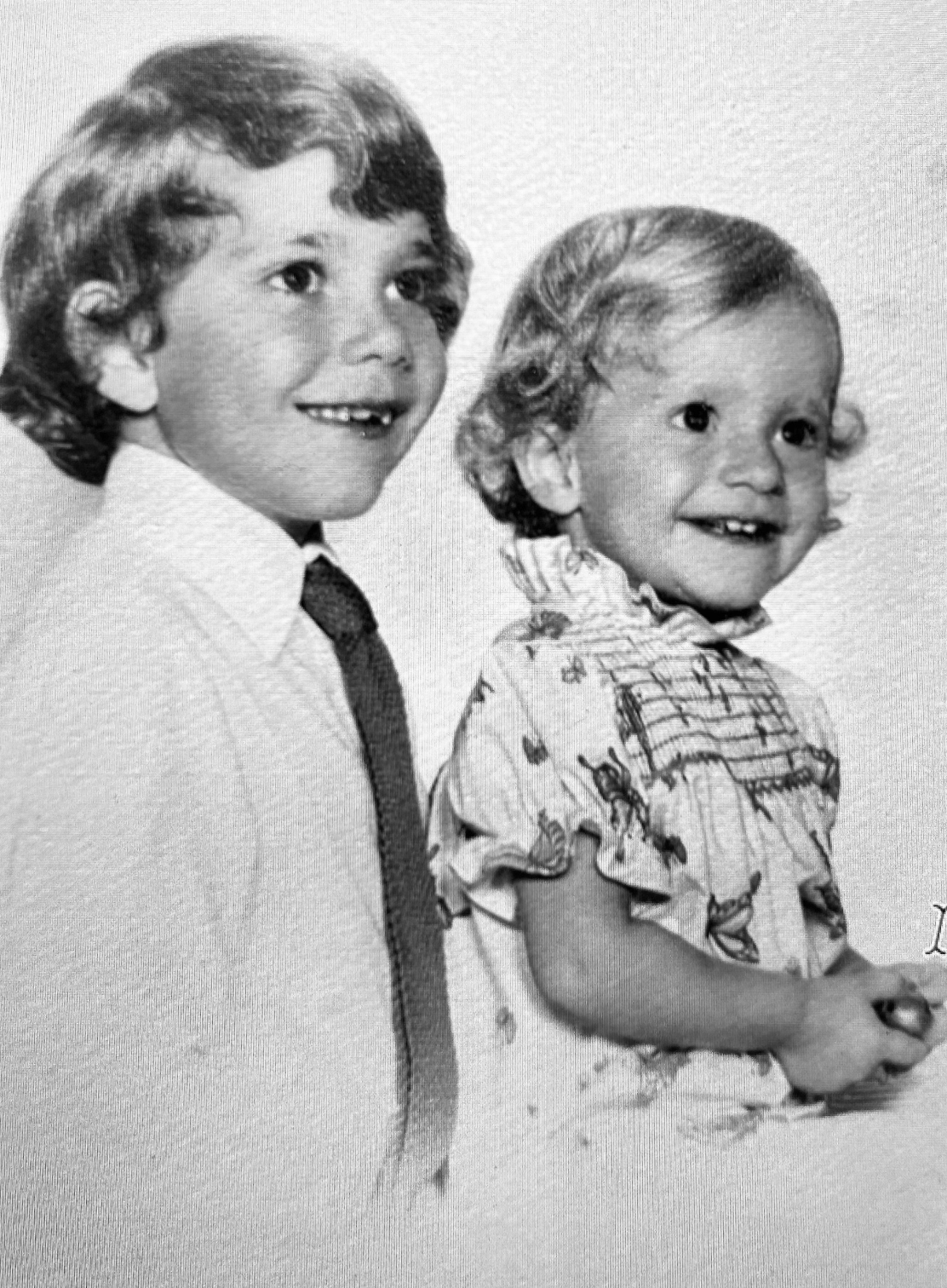

Chris and Sarah 1971

Chris and Catherine 1976

1972

Lying in bed, I probe the four small gouges in my belly, uneasily close to the intestinal me. Discreetly faded now and covered by all but the most advanced in swimwear, those stretch marks seemed devastating when they opened up in the second trimester. Purple, jagged, they were the first permanent scarring, aging, the irremediable made flesh. Sarah left these stretch marks on me, and they take me back into the physical and psychological reality of my second pregnancy.

I remember the nausea, the inability to imagine any food I would care to come within a mile of, living on china tea and sleep, at the mercy of any stray cooking smell. Yet the most frightening part of that three-month misery was not the physical weakness but the almost total clampdown on the mental processes. Today I can reflect on myself. Then I was wholly prey to sensations. Perhaps that is what contingency is all about, loss of the illusion of control, one’s inner emptiness helpless before the assault of the outside world.

And it was so unexpected, so sudden. The beginnings of my first child, Christopher, had cut my appetite and weight, no mean advantage in a modern pregnancy, but the second’s brought me close to collapse. As dramatically disabling and as mysterious as in a Victorian novel, this pregnancy was a weird memento mori, accelerating the body’s capacity to change, stressing its control of the mind. Compared to this experience, everything written about motherhood seemed absurdly schematic and trite, the work of men or childless women. Must a woman choose between writing books and bearing children, I wondered, and can that choice be a free one? Is she even aware of it?

Then, once the nausea subsided, what I I remember is feeling overwhelmed because I was responsible for the health and intelligence of another being and yet unable to exert much control. The memory of a cousin and a friend, the sight of some children in the park, all these showed me that the blind, the lame and the mentally handicapped are not figments of the female imagination. The pictures of the babies deformed by thalidomide were fresh in my mind, so I avoided medications. and threw myself passionately upon those aspects of pregnancy where wit and will can play a part: quarts of milk, dozens of eggs, multi- vitamins. Pictures of women cocooned up to their chests in monstrous vacuum bags, oxygen pumping into their deteriorating placentas, filled me with desire and envy. As for the process of birthing a child, psychoprophylaxis had won my absolute intellectual support, I had trained for the job, and talk of anesthesia, of not wanting to know about labour, filled me with contempt for my sex.

But as the seventh month of my second pregnancy waned, I started to worry less about the child and more about myself. I had put the memory of my first delivery behind me but now the memories were creeping back, and I was afraid.

If only those stupid ignorant women would stop being afraid and so damned civilized, the British childbirth guru Grantly Dick Read had opined, everything would be fine and dandy. But painless childbirth was a myth, and I knew it. Twenty-six hours in labour in the maternity ward at Cambridge General Hospital in England had been no fun, and I had not started out afraid. Three of my closest friends had mentioned having difficult, painful experiences when giving birth but this did nothing to impair my blithe assurance of personal indemnity. I would not have painkillers, I would not scream like a cow in an abattoir, the self-description of one humorous buddy of her labour, because it wasn’t going to hurt me. Contractions, definitely, not pains.

My first few hours of labour were exhilarating. I breezed into the hospital, breathing superbly, more distressed by the obligatory enema than the cramps. Routinely shot with pentathol, I refused sleep and completed the Guardian crossword with Mike in fine style. The night was already different. Only two nurses for a large ward of labourers, no company allowed after midnight, continuing strong contractions, no dilation-when anyone bothered to measure it. Another pentathol shot around 5 a.m. gratefully received, throbbing sleep broken at six for the regulation wash and a cup of tea which I refused to drink. I had neither time nor energy for throwing up, and my stomach had closed off.

Mike fought his way back into the ward, timed my contractions, defended me from the well-meaning interference of nurses totally unacquainted with the Natural Childbirth method and trained to reject the unknown. But after a whole day in vigorous labour, my inner resources were rapidly drying up. I lay there, watching the clock tick round, 15, 20 seconds, another contraction coming already, panting like a demented steam engine, using the last-ditch exercise and failing. Someone help me. Please stop it. I can’t bear it anymore. The transition phase is often difficult, the book had said, but correlating those words and that experience was even more so.

By comparison, the last stage was an agonizing relief. Sitting on the delivery table, unsupported by the mass of pillows provided in all the textbook hospitals, gripping my knees, I remember Mike, cox, cheer leader, shouting “Push” and feeling, as I held my breath and bore down, that this was the most heroic thing I had ever done. That huge ball tearing me apart, as it moved down, the blood from my hand shooting up the tube of the partially disconnected sugar-drip, a reprimand for touching the crowning head with an un-sterile hand. My baby, who had been turned twice under anesthesia in his fifth and sixth month in utero, was finally right side down and the nurses dealt competently with the umbilical cord wrapped twice around his neck.

Me and Chris about half an hour post partum. No funny little hats for newborns in British hospitals in 1972.

The staff needed the delivery room urgently so, after sewing me up and cleaning me and baby off a bit, they sent Mike home and Chris and I were wheeled off in different directions. It was about three a.m. too early to go into the regular ward, so I found myself,, exhausted but exhilarated, back in the labor ward where I lay awake listening to the frantic screams of a young woman. She was presumably in the early stages of labour so the nurses were too busy to bother with her. I longed fiercely to have the strength to get up and hold her hand and help her do the breathing that had helped me. I was grateful as never before for my intelligent mind and for being at least dimly aware of the possible repercussion upon me personally of the much-canvassed problems of under-staffing in state hospitals.

Next morning, I was in the post-delivery ward, made clean and presentable in my new, sexy nightie, and baby finally in my arms.

We and the hospital were now ready to welcome Mike in his traditional role of beaming new father, but for us it was a tense meeting. I had delivered our baby ten days later than we had planned, so Mike was off that day to Dover and the liner on which he and all our belongings would sail to Boston. Being homeless, for two weeks I was stuck by National Health regulations in the maternity ward, pissing off the nursery staff s by my unavailing attempts to get my baby to latch onto a pair of nipples that anyone could see were sub-standard We had no friends in Cambridge now so my only visitor was my sister Rose, now a Cambridge undergraduate, who loyally biked all across town to listen to me weeping and Christopher howling and bring me the clean nighties and underwear she had washed in the New Hall machines. That was the beginning of the real love and understanding between me and my sister.

Things took a decided turn for the better when my parents drove over from Cardiff to take me and baby Chris, now thriving on Ostermilk, for a happy three weeks.

Cardiff, October 1967. Me, Mummy, Nana, and Chris, first grandchild and great grand child

I then went to London to stay with my mother-in—law, and, since I was still bleeding heavily, got an appointment with her doctor. This man had no advice but took out my stitches and proved to be very interested indeed in giving me a complete physical examination. This was my first, and luckily my only, experience of medical malpractice. Finally, five weeks postpartum, I set off for the United States carrying Chris in a Moses basket., ready to face my life as a new mother in a new country.

For two years, I put the memory of my first delivery away, as women do. If an anxious girl friend asked me about Chris’s birth, I refused, humorously, to elaborate. Everything had, after all, turned out fine. I could feel pride that, with the support of my husband, Dr Read’s breathing exercises, and not much else, I had propelled a child into existence without anesthesia, and Mike and I had produced a pretty terrific kid. So, when Mike suggested it was time we tried for number two. I agreed, once again without a moment’s thought, and, once again, within a month, I was pregnant again, and as my delivery date approached, memories of pain seeped back in. Despite all the careful decisions and preparations that I had made for the birth, I felt fear. There was now no choice. This baby would have to come out of me, and I would lose control over what was happening to us both. I began to have dreams in which the being inside me was not a baby but a toddler, a child even, dreams in which I bypassed all the hurdles of childbirth, bleeding, lactation.

As it turned out, my daughter Sarah’s birth was a glorious satisfaction Far from painless, but controlled, swift, companionable. I was not in a big ward but in in a private room where Mike was welcome by the charming and attentive nurses, and my wonderful American obstetrician Dr, Yahia arrived at just the right moment to put in his hand, turn the baby’s head and slide her out without anesthesia or stitches. Six days after delivery, I was able to ride my bicycle to the Harvard Commencement. No wonder I loved my daughter. All the fear, the anxiety, the indifference had been swept away as she was put into my arms, bawling spontaneously, the wet cord trailing over my deflated abdomen. I’d so wanted a girl, and had been so sure of disappointment, so calculatedly turned off by anything under a year old. She was never to be a disappointment, growing like a pumpkin, sleeping like a log, hairless and toothless, a gay, plump, adventurous little person who was killed before she found anyone in the world more important than Mum.

Sarah and me at Christmas 1970, in my home in Cardiff.

Lying in bed, thinking, feeling those almost imperceptible scars on my belly, I realize that they are the last remaining marks of her presence in the world, and I weep for my baby. Mainly, my tears are for her, so marvelously made for living and enjoying life. I cannot believe in angels. For myself, there is the feeling of radical incompleteness, a mental scar, invisible to the world that time cannot fade. But in me there is also a joy, an ineradicable conviction that she was a plus that can never be subtracted from my life, that the eight months gift of her life was worth all the labour pains.